LawFlash

Federal Circuit Weighs in on Prosecution History Estoppel Applied to Design Patents

August 06, 2018Applicants should consider how including multiple embodiments in a design patent application may later impact the scope of protection.

In Advantek Mktg. v. Shanghai Walk-Long Tools [1], the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit revived a patent lawsuit against a product manufacturer over the design of a pet kennel. In a precedential opinion, the court found the district court wrongly applied prosecution history estoppel in granting the defendant’s motion for judgement on the pleadings.

The Prosecution History

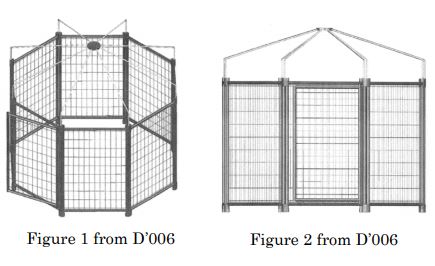

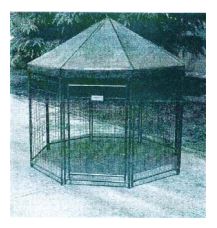

Advantek filed a design patent application directed to its flagship product, the “Pet Gazebo.” The application included Figures 1-4 – a kennel without a cover, and Figure 5 – the kennel of Figures 1-4 with a cover.

Figs. 1 and 2[2]

Fig. 5

In the first action issued from the US Patent and Trademark Office, the examiner objected to the clarity of the drawings and issued a restriction requirement as between Group I (Figs. 1-4, drawn to a kennel without a cover) and Group II (Figs. 1-5 drawn to a kennel with a cover). The examiner asserted that the two groups are distinct embodiments and stated that the single claim requirement of a design patent bars the inclusion of figures having distinct combinations of elements. Advantek elected Group I, submitted clearer drawings, and withdrew Group II. The application proceeded to grant with Figure 5 being cancelled from the application.

The Litigation

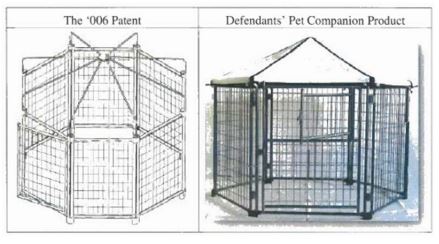

Advantek filed a design patent infringement lawsuit in May 2016, accusing Walk-Long of copying the Pet Gazebo, and making its own kennel, the “Pet Companion.” Walk-Long is a former manufacturer of the Pet Gazebo for Advantek.

Fig. 1 of the Advantek Patent Walk-Long’s Pet Companion

The district court ruled in favor of Walk-Long in November 2016, finding that Advantek was barred from enforcing its patent against Walk-Long’s Pet Companion, which has a roof. The court held that because Advantek surrendered the roof embodiment during prosecution, it was barred from enforcing its patent against a product with a roof due to the doctrine of prosecution history estoppel.

On appeal, Advantek argued that the claimed design without a cover is present in the accused Pet Companion, and that the cover is merely an extra unclaimed feature. Advantek further argued that the elected embodiment is broader than the non-elected embodiment and that prosecution history estoppel only arises when an amendment is made to secure the patent and that amendment narrows the patent’s scope.[3]

The Federal Circuit sided with Advantek and stated that regardless of whether Advantek surrendered claim scope during prosecution by cancelling the embodiment directed to a kennel with a roof, the accused product includes the particularly claimed skeletal structure and was outside the scope of the purported surrender. The Federal Circuit stated that infringement arises from the sale of a kennel embodying the patent structural design, “regardless of the extra features [i.e., the added roof].”

In an interesting aside, the Federal Circuit noted that “if the accused skeletal structure is only a component of an accused multicomponent product, Advantek would only be able to seek damages based on the value of the component, not the product as a whole.”[4]

Considerations in Light of Advantek Mktg.

While prosecution history estoppel did not bar infringement in this particular instance, Advantek was fortunate that the elected embodiment is similar to the accused product and the difference from the elected embodiment as compared to the unelected embodiment was only the removal of an additional feature. However, whether an elected embodiment is considered broader or narrower as compared to non-elected embodiments may not always be as apparent and prosecution history estoppel may be found.

Prior to prosecuting design patent applications with multiple embodiments, applicants should consider the impact that a future restriction and election may have on enforceability and recovery of damages.

Contacts

If you have any questions or would like more information on the issues discussed in this LawFlash, please contact the author, John Hemmer in our Philadelphia office, or any of the following lawyers:

Boston

Joshua M. Dalton

Chicago

Scott D. Sherwin

Jason C. White

Houston

C. Erik Hawes

Philadelphia

Kenneth J. Davis

Louis W. Beardell, Jr.

San Francisco

Brett A. Lovejoy, Ph.D.

Carla B. Oakley

Silicon Valley

Dion M. Bregman

Douglas J. Crisman

Andrew Gray IV

Michael J. Lyons

Washington, DC

Eric S. Namrow

Collin W. Park

[1] No. 2017-1314, slip op. at 8 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 1, 2018).

[2] Drawings as amended. Figs. 3 and 4 are directed to the top and bottom views respectively and are not shown here.

[3] Festo Corp. v. Shoketsu Kinzoku Kogyo Kabushiki Co., 535 US 722, 736 (2002).

[4] Advantek Mktg., Inc. v. Shanghai Walk-Long Tools, No. 2017-1314, slip op. at 9 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 1, 2018)(emphasis added).