LawFlash

SEC Proposes Rules of the Road for Brokers Giving Advice to Retail Investors

May 15, 2018This LawFlash analyzes the key aspects and questions raised by proposed Regulation Best Interest, including its impact on broker-dealers from disclosure, compliance, and operational perspectives.

As described in our prior LawFlash, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) voted 4‑1 to propose “Regulation Best Interest” as part of a package of proposed rulemaking and interpretive guidance on the standards of conduct for broker-dealers and investment advisers. Regulation Best Interest would require a broker-dealer or a natural person who is an associated person of the broker-dealer (Registered Representative), “when making a recommendation of any securities transaction or investment strategy involving securities to a retail customer, [to] act in the best interest of the retail customer at the time the recommendation is made, without placing the financial or other interest of the [broker-dealer or Registered Representative] making the recommendation ahead of the interest of the retail customer” (the Best Interest Obligation).[1] Unless the comment period is extended, comments on the SEC proposals are due by August 7, 2018.

As proposed, Regulation Best Interest would have a profound impact on broker-dealers from disclosure, compliance, and operational perspectives. A broker-dealer would be deemed to satisfy the Best Interest Obligation if it fulfills (1) a disclosure obligation, (2) a duty of care obligation, and (3) a conflict of interest obligation.

The SEC has not proposed to define “best interest,” and the vagaries of this concept sparked dialogue among the Commissioners at the open meeting.[2] According to the SEC in its release, “whether a broker-dealer acted in the best interest of the retail customer when making a recommendation will turn on the facts and circumstances of the particular recommendation and the particular retail customer, along with the facts and circumstances of how the . . . components of Regulation Best Interest are satisfied.”[3]

Some of the key questions raised by proposed Regulation Best Interest include:

- What does it mean to act in a retail customer’s “best interest?”

- Is “best interest” consistent with current interpretations of a broker-dealer’s suitability obligations, or does it require something more? If something more, what does it require?

- How does the new “best interest” concept impact the sale of proprietary products or a limited range of products?

- Which conflicts can be disclosed and mitigated, and which must be eliminated?

- To what extent does the proposal reflect a repackaging of the recently vacated US Department of Labor’s (DOL) Fiduciary Rule and Best Interest Contract Exemption?

Below we discuss key definitional issues about when the Best Interest Obligation applies and describe the components of the Best Interest Obligation. We also highlight areas where broker-dealers would benefit from additional clarity from the SEC, both on when the Best Interest Obligation applies and the scope of its requirements.

When Does the Best Interest Obligation Apply?

As proposed, the Best Interest Obligation would apply when a broker-dealer or Registered Representative (1) makes a recommendation (2) of any securities transaction or investment strategy involving securities (3) to a retail customer. According to the SEC, the obligation would not:

- extend beyond a particular recommendation, generally require a broker-dealer to have a continuous duty to a retail customer, or impose a duty to monitor the performance of the account;

- apply to self-directed or otherwise unsolicited transactions by a retail customer; or

- require that the broker-dealer refuse a customer’s order that is contrary to the broker-dealer’s recommendations.

According to the SEC, the Best Interest Obligation would not apply to the relationship between an investment adviser and its clients, and a dual-registrant would be required to comply with Regulation Best Interest only when making a recommendation in its capacity as a broker-dealer.

What Is a Recommendation?

The SEC has not proposed to define “recommendation” for purposes of Regulation Best Interest. Instead, the SEC would interpret the concept of a recommendation and whether one has been made consistent with existing broker-dealer regulation under the federal securities laws and Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) Rule 2111, which look to the facts and circumstances of a particular communication. The SEC believes this approach will provide clarity to broker-dealers by allowing them to rely on existing guidance and interpretations. The SEC also stated that, consistent with FINRA Rule 2111, certain communications would generally not constitute recommendations as long as they do not include (standing alone or in combination with other communications) a recommendation of a particular security or securities. In addition, the SEC stated that providing general investor education (e.g., a brochure discussing asset allocation strategies) or limited investment analysis tools (e.g., a retirement savings calculator) would not be recommendations.

What Is a Securities Transaction or Investment Strategy Involving Securities?

The Best Interest Obligation would apply to recommendations of any purchase, sale, or exchange of a security or investment strategy (including explicit recommendations to hold a security or the manner in which a security is to be purchased or sold) to retail customers. The SEC has not proposed to extend the Best Interest Obligation to recommendations of account types generally (i.e., whether to have a brokerage or advisory relationship), but the Best Interest Obligation would apply to recommendations to transfer or roll over assets from one account type to another where the recommendation is tied to a securities transaction (e.g., IRA rollovers).

What Is a Retail Customer?

The SEC has proposed to define “retail customer” as a person, or the legal representative of the person, who receives a recommendation of any securities transaction or investment strategy involving securities from a broker-dealer or Registered Representative, and “[u]ses the recommendation primarily for personal, family, or household purposes.”[4] As proposed, the definition is broader than that in Section 913 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act) in that it extends to non-natural persons that the SEC believes would benefit from the protections of Regulation Best Interest (such as trusts that represent the assets of a natural person), provided the recommendation is used primarily for personal, family, or household purposes.[5]

Initial Observations

Despite the SEC’s efforts to align Regulation Best Interest to existing broker-dealer standards, significant differences remain. For example, the proposed definition of “retail customer” would carve back the institutional suitability safe harbor provision of FINRA Rule 2111—approved by the SEC—which effectively relieves a broker-dealer of customer-specific suitability obligations when making recommendations to natural persons (and trusts) who have total assets of at least $50 million and have opted out of the rule’s protection, without regard to whether the recommendation is to be used for personal, family, or household purposes. In comparison, proposed Regulation Best Interest would apply to a recommendation to such ultra-high net worth persons, including entities (which are also persons for purposes of the Exchange Act) if the recommendation is used primarily for personal, family, or household purposes.

Questions might also arise as to when a recommendation would be used “primarily for personal, family or household purposes,” as opposed to business or commercial purposes. In the proposing release, the SEC stated that the definition would not include recommendations related to business or commercial purposes, but without providing additional guidance.[6] The proposed definition of retail customer also raises questions about whether broker-dealers would be subject to an ex-post review of how recommendations are used by a person, rather than looking to the reasonable expectations of the broker-dealer and the person at the time a recommendation is made. For example, a person that receives a recommendation in one context, such as for business or commercial purposes, could potentially be deemed a “retail customer” if the person also uses the recommendation for personal, family, or household purposes. Broker-dealers would benefit from greater clarity, including through examples included in the rule itself, about when a person is a retail customer, both in regard to natural person and non-natural person customers.

Broker-dealers seeking to comply with both Regulation Best Interest and Form CRS would face compliance and operational issues because of the inconsistent definitions of “retail customer” under Regulation Best Interest and “retail investor” for purposes of Form CRS.

|

Regulation Best Interest – |

Form CRS – |

|

Retail Customer means a person, or the legal representative of such person, who: (A) Receives a recommendation of any securities transaction or investment strategy involving securities from a broker, dealer, or a natural person who is an associated person of a broker or dealer; and (B) Uses the recommendation primarily for personal, family, or household purposes. |

Retail investor means a client or prospective client who is a natural person (an individual). This term includes a trust or other similar entity that represents natural persons, even if another person is a trustee or managing agent of the trust. |

Designing compliance and operational approaches around the inconsistent definitions would appear to create unnecessary complications and additional expenses for broker-dealers.

Moreover, as proposed, it is unclear whether an investment adviser or other financial intermediary would be viewed as a legal representative of a natural person, such that recommendations a broker-dealer makes to the intermediary would be subject to the Best Interest Obligation. We note that the DOL included a helpful carve-out from the fiduciary rule for advice to certain financial intermediaries (such as banks, broker-dealers, and insurance carriers) as well as independent plan fiduciaries managing or controlling assets of at least $50 million. Broker-dealers would benefit from clarity that recommendations provided to a financial intermediary are excluded from the requirements of proposed Regulation Best Interest, especially where the financial intermediary is itself subject to suitability obligations when acting for its natural person customers or clients.[7]

Finally, the SEC’s statement that more general communications that are not typically recommendations by themselves could nonetheless be viewed as recommendations when they form part of the mosaic of a recommendation (such as that arising in a later communication) could be problematic because the earlier and more general communications would typically neither be crafted nor intended as a customer-specific recommendation. As such, they would not be amenable to the tailored conflict-based disclosures or otherwise circumscribed to address conflicts as contemplated by proposed Regulation Best Interest. We also note that the DOL took a similar approach to relying on FINRA guidance in defining the types of communications that would be viewed as “recommendations” that triggered fiduciary status under the fiduciary rule.

How Does a Broker-Dealer Satisfy the Best Interest Obligation?

As mentioned above, the Best Interest Obligation would require a broker-dealer or Registered Representative, “when making a recommendation of any securities transaction or investment strategy involving securities to a retail customer, [to] act in the best interest of the retail customer at the time the recommendation is made, without placing the financial or other interest of the [broker-dealer or Registered Representative] making the recommendation ahead of the interest of the retail customer.” According to the SEC, Regulation Best Interest would prohibit a broker-dealer from making its financial interests the “predominant motivating factor behind a recommendation” and from putting its interests ahead of the retail customer’s.

A broker-dealer would be deemed to satisfy the Best Interest Obligation if it fulfills (1) a disclosure obligation, (2) a duty of care obligation, and (3) a conflict of interest obligation. The SEC stated that neither the broker-dealer, the Registered Representative, nor the retail customer would be permitted to waive the broker-dealer’s or Registered Representative’s compliance with the Best Interest Obligation, and the broker-dealer or Registered Representative would not otherwise be able to reduce the scope of the Best Interest Obligation, such as by contract.

What Does the Disclosure Obligation Require?

The Disclosure Obligation would require that a broker-dealer or Registered Representative, “prior to or at the time of [making a] recommendation, reasonably discloses to the retail customer, in writing, the material facts relating to the scope and terms of the relationship with the retail customer, including all material conflicts of interest that are associated with the recommendation.”[8] Because broker-dealers are not currently subject to an explicit and broad disclosure requirement under the Exchange Act, the SEC perceives the Disclosure Obligation as an important way to facilitate retail customers’ awareness of certain key information regarding their relationship with the broker-dealer and to avoid investor confusion. Below we discuss (1) what material facts must be disclosed and (2) what it means to “reasonably disclose” the material facts.

What Material Facts Must Be Disclosed?

According to the SEC, the material facts a broker-dealer would need to reasonably disclose include “all material conflicts of interest associated with the recommendation” and “(i) that the broker-dealer is acting in a broker-dealer capacity with respect to the recommendation; (ii) fees and charges that apply to the retail customer’s transactions, holdings, and accounts; and (iii) type and scope of services provided by the broker-dealer, including, for example, monitoring the performance of the retail customer’s account.” The SEC intends to permit broker-dealers to use a “layered approach” in disclosing material facts about recommendations, including by building on proposed Form CRS. According to the SEC, the Disclosure Obligation would not be met solely by satisfying the proposed Form CRS requirements also proposed on April 18, 2018.[9] Rather, the Disclosure Obligation is intended to build on and supplement disclosure made on Form CRS.

Material Conflicts of Interest: For purposes of the Best Interest Obligation, a “material conflict of interest” would be one “that a reasonable person would expect might incline a broker-dealer—consciously or unconsciously—to make a recommendation that is not disinterested.” According to the SEC, Regulation Best Interest is not intended to, and “would not per se,” prohibit the following conflicts:

- Charging commissions or other transaction-based fees;

- Receiving or providing differential compensation based on the product sold;

- Receiving third-party compensation;

- Recommending proprietary products;

- Recommending products of affiliates;

- Recommending a limited range of products;

- Recommending a security underwritten by the broker-dealer or an affiliate, including initial public offerings (IPOs);

- Recommending a transaction to be executed in a principal capacity;

- Recommending complex products;

- Allocating trades and research, including allocating investment opportunities (e.g., IPO allocations or proprietary research or advice) among different types of customers and between retail customers and the broker-dealer’s own account;

- Considering cost to the broker-dealer of effecting the transaction or strategy on behalf of the customer (e.g., the effort or cost of buying or selling an illiquid security); or

- Accepting a retail customer’s order that is contrary to the broker-dealer’s recommendations.

However, the SEC stated that it preliminarily believes that the following material conflicts of interest would need to be disclosed:

- Recommending proprietary products;

- Recommending products of affiliates;

- Recommending a limited range of products;

- Recommending one share class of a security over another share class of the same security;

- Recommending securities underwritten by the broker-dealer or an affiliate;

- Recommending the rollover or transfer assets from one type of account to another that involves a securities transaction; and

- Allocating investment opportunities (e.g., IPOs) among retail customers.

Capacity: For a broker-dealer that is not dually registered as an investment adviser, the SEC would not expect that a broker-dealer or its Registered Representatives repeat the capacity disclosures made pursuant to Form CRS. However, a dual-registrant would be expected to provide retail customers with additional disclosures that make clear the capacity in which the dual-registrant is acting “at the time” of making recommendations. According to the SEC, a dual-registrant could disclose its capacity through written disclosure at the outset of a relationship (e.g., in an account opening agreement or account relationship disclosure) that clearly sets forth when the dual-registrant would act in a broker-dealer capacity and how it will provide notification of any changes in capacity. For example, the SEC stated that the agreement or disclosure might state that:

- “All recommendations will be made in a broker-dealer capacity unless otherwise expressly stated at the time of the recommendation”; or

- “All recommendations regarding your brokerage account will be made in a broker-dealer capacity, and all recommendations regarding your advisory account will be in an advisory capacity. When we make a recommendation to you, we will expressly tell you which account we are discussing and the capacity in which we are acting.”

The SEC indicated that it preliminarily believes that a dual-registrant that provides this type of disclosure would not need to provide written disclosure each time it changes capacity or makes a recommendation. Interestingly, the SEC avoided taking the approach the Division of Investment Management staff took in a December 16, 2005, letter to the Securities Industry Association with respect to “hat switching” that focused on whether the disclosure was “sufficient to enable the client to reasonably understand that the broker-dealer/investment adviser is removing itself from a position of trust and confidence with its client.”[10]

Fees and Charges: Because Form CRS requires high-level disclosures in broad categories, but not specific amounts of fees and charges, the Disclosure Obligation will generally require a broker-dealer to supplement the Form CRS summary information by disclosing additional detail (including quantitative information, such as amounts, percentages, or ranges) of the types of fees and charges.

Type and Scope of Services: The SEC similarly believes that, under the Disclosure Obligation, a broker-dealer should supplement Form CRS disclosures and provide more information about the types of services to be provided and the scope of those services.

What Does the SEC Mean by “Reasonably Disclose”?

The SEC stated that, “[i]n order to ‘reasonably disclose’ in accordance with the Disclosure Obligation, a broker-dealer would need to give sufficient information to enable a retail customer to make an informed decision with regard to the recommendation.” In addition, the disclosure “must be true and may not omit any material facts necessary to make the required disclosures not misleading.”

Form and Manner of Disclosure: The SEC has not proposed to prescribe the form or manner of disclosure, and instead proposes to provide broker-dealers with flexibility on how to satisfy the Disclosure Obligation taking into account their business practices. Despite the flexibility, the SEC indicated that it believes the adequacy of disclosure will ultimately depend on the facts and circumstances and will be judged against a negligence standard (not strict liability). According to the SEC, the disclosure should (i) be concise, clear, and understandable; (ii) be written in “plain English,” using short sentences and active voice; and (iii) avoid legal jargon, highly technical business terms, and multiple negatives. The SEC stated that delivery of the disclosure could be effected pursuant to the SEC’s guidance on electronic delivery of documents (although the SEC curiously did not mention the Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce Act, or E-SIGN).

Timing and Frequency of Disclosure: In the SEC’s view, investors should receive information early enough in the process to give them adequate time to consider and understand the information in order to make informed investment decisions, but not so early that the disclosure fails to provide meaningful information (e.g., does not sufficiently identify material conflicts presented by a particular recommendation, or overwhelms the retail customer with disclosures related to a number of potential options that the retail customer may not ultimately be qualified to pursue). The SEC provided examples of four approaches broker-dealers might consider in providing timely disclosures:

- “at the beginning of a relationship (e.g., in a relationship guide, such as or in addition to the Relationship Summary, or in written communications with the retail customer, such as the account opening agreement)”;

- “on a regular or periodic basis (e.g., on a quarterly or annual basis, when any previously disclosed information becomes materially inaccurate, or when there is new relevant material information)”;

- “at other points, such as before making a particular recommendation or at the point of sale”; and

- “at multiple points in the relationship or through a layered approach to disclosure”.

The SEC stated that disclosure after the recommendation, such as in a trade confirmation for a particular recommended transaction would not, by itself, satisfy the Disclosure Obligation, because the disclosure would not be “prior to, or at the time of the recommendation.” However, according to the SEC, a broker-dealer could satisfy the Disclosure Obligation, depending on the facts and circumstances, if the initial disclosure, in addition to conveying material facts relating to the scope and terms of the relationship with the retail customer, explains when and how a broker-dealer would provide additional, more specific information regarding the material fact or conflict in a subsequent disclosure (e.g., disclosures in a trade confirmation concerning when the broker-dealer effects recommended transactions in a principal capacity). The SEC also emphasized that, where a significant amount of time passes between the disclosure and a recommendation, the broker-dealer generally would need to determine whether the retail customer should reasonably be expected to be on notice of the prior disclosure and, if not, the broker-dealer generally should not rely on such disclosure.

What Does the Care Obligation Require?

Under Regulation Best Interest, a broker-dealer would be required to exercise “reasonable diligence, care, skill, and prudence” to:

- “Understand the potential risks and rewards of the recommendation and have a reasonable basis to believe that the recommendation could be in the best interest of at least some retail customers” (Reasonable-Basis Obligation);

- “Have a reasonable basis to believe that the recommendation is in the best interest of a particular retail customer based on that retail customer’s investment profile and the potential risks and rewards associated with the recommendation” (Customer-Specific Obligation); and

- “Have a reasonable basis to believe that a series of recommended transactions, even if in the retail customer’s best interest when viewed in isolation, is not excessive and is in the retail customer’s best interest when taken together in light of the retail customer’s investment profile” (Quantitative Obligation).[11]

According to the SEC, the components of the Care Obligation are intended to incorporate and build on existing reasonable-basis, customer-specific, and quantitative suitability obligations under the antifraud provisions of the federal securities laws and FINRA Rule 2111 “by, among other things, imposing a ‘best interest’ requirement” that the SEC “would interpret to require the broker-dealer not put its own interest ahead of the retail customer’s interest, when making recommendations.” The SEC stated, however, that a key difference is that, unlike existing suitability obligations under the antifraud provisions of the federal securities laws, the Care Obligation would not require scienter and could not be satisfied through disclosure.[12]

What Is the Reasonable-Basis Obligation?

The SEC stated that, similar to existing suitability obligations, what would constitute reasonable diligence would “vary depending on, among other things, the complexity of and risks associated with the recommended security or investment strategy and the broker-dealer’s familiarity with the recommended security or investment strategy.” The SEC identified the following factors as potentially relevant: cost, investment objectives, characteristics, liquidity, risks, potential benefits, volatility, likely performance of market and economic conditions, expected return, and financial incentives to recommend the security or investment strategy. In addition, the SEC provided some questions that broker-dealers might consider in reviewing a security or investment strategy:

- “Can less costly, complex, or risky products available at the broker-dealer achieve the objectives of the product?”

- “What assumptions underlie the product, and how sound are they? What market or performance factors determine the investor’s return?”

- “What are the risks specific to retail customers? If the product was designed mainly to generate yield, does the yield justify the risk to principal?”

- “What costs and fees for the retail customer are associated with this product? Why are they appropriate? Are all of the costs and fees transparent? How do they compare with comparable products offered by the firm?”

- “What financial incentives are associated with the product, and how will costs, fees, and compensation relating to the product impact an investor’s return?”

- “Does the product present any novel legal, tax, market, investment, or credit risks?”

- “How liquid is the product? Is there a secondary market for the product?”

What Is the Customer-Specific Obligation?

As mentioned above, the Customer-Specific Obligation would require a broker-dealer to have a reasonable basis to believe that the recommendation is in the “best interest” of the particular retail customer to whom it is made based on the retail customer’s investment profile and the potential risks and rewards associated with the recommendation.[13] According to the SEC, a broker-dealer would not satisfy the Customer-Specific Obligation if the broker-dealer puts its interest ahead of the retail customer’s interest.

Under the Care Obligation, a broker-dealer generally would need to consider reasonable alternatives, if any, to be offered by the broker-dealer in determining whether it has a reasonable basis for making the recommendation. The SEC stated that this approach would not require a broker-dealer to analyze all possible securities, to recommend the single “best” security, or necessarily to recommend the least expensive or least remunerative security or investment strategy. In addition, the SEC stated that it does not view Regulation Best Interest as prohibiting, among others, recommendations from a limited range of products, or recommendations of proprietary products, products of affiliates, or principal transactions, if the Care Obligation is satisfied and the associated conflicts are disclosed (and mitigated, as applicable) or eliminated.

Notwithstanding these general statements, the SEC believes cost “would generally be an important factor” under the Care Obligation. In this regard, the SEC stated that a broker-dealer that recommends a more-expensive security “would need to have a reasonable basis to believe that the higher cost of the security or strategy is justified (and thus nevertheless in the retail customer’s best interest) based on other factors . . . in light of the retail customer’s investment profile.” In the SEC’s view, “a broker-dealer could not have a reasonable basis to believe that a recommended security is in the best interest of a retail customer if it is more costly than a reasonably available alternative offered by the broker-dealer and the characteristics of the securities are otherwise identical.” In addition, the SEC stated that a recommendation would be inconsistent with the Care Obligation if it were made to maximize the broker-dealer’s compensation, further its business relationships, satisfy firm sales quotas or other targets, or win a firm-sponsored sales contest.

What Is the Quantitative Obligation?

The SEC stated that the proposed Quantitative Obligation is intended to incorporate and enhance existing quantitative suitability obligations, but would expand its application beyond situations in which the broker-dealer has actual or de facto control over an account. As a result, the obligation would extend to all trades in a retail customer’s account that result from a broker-dealer’s recommendation, irrespective of whether the broker-dealer exercises control over the retail customer’s account.[14]

What Does the Conflict of Interest Obligation Require?

The Conflict of Interest Obligation consists of two components. As a general matter, a broker-dealer must “establish[], maintain[], and enforce[] written policies and procedures reasonably designed to identify and at a minimum disclose, or eliminate, all material conflicts of interest that are associated with such recommendations” that are subject to Regulation Best Interest.[15] In addition, however, the broker-dealer’s policies and procedures would need to be “reasonably designed to identify and disclose and mitigate, or eliminate, material conflicts of interest arising from financial incentives associated with such recommendations.”[16]

In the SEC’s view, a broker-dealer would be permitted to exercise its own judgment as to whether a conflict can be effectively disclosed or whether it should be eliminated. Similarly, material conflicts of interest arising from financial incentives would not need to be eliminated, but a broker-dealer that does not eliminate those material conflicts would need to adopt policies and procedures designed to disclose and mitigate them. According to the SEC, material conflicts arising from financial incentives generally would include, but would not be limited to:

- “receipt of commissions or sales charges, or other fees or financial incentives, or differential or variable compensation, whether paid by the retail customer or a third party”;

- “sales of proprietary products or services, or products of affiliates”;

- “compensation practices established by the broker-dealer, including fees and other charges for the services provided and products sold”;

- “employee compensation or employment incentives (e.g., quotas, bonuses, sales contests, special awards, differential or variable compensation, incentives tied to appraisals or performance reviews)”;

- “compensation practices involving third parties, including both sales compensation and compensation that does not result from sales activity, such as compensation for services provided to third parties (e.g., sub-accounting or administrative services provided to a mutual fund)”; and

- “transactions that would be effected by the broker-dealer (or an affiliate thereof) in a principal capacity.”

To satisfy the Conflict of Interest Obligation, a broker-dealer’s policies and procedures would need to be “reasonably designed.” The SEC believes that a broker-dealer could use a risk-based compliance and supervision system to focus on specific areas of its business that pose the greatest risk of noncompliance with the Conflict of Interest Obligation and the greatest risk of potential harm to retail customers. In this regard, broker-dealers might be able to build upon existing risk-based approaches to compliance with FINRA Rule 2111. In the SEC’s view, a broker-dealer should consider, among others, the following components in its compliance program:

- “policies and procedures outlining how the firm identifies its material conflicts (and material conflicts arising from financial incentives),” which should generally:

- define material conflicts in a way that is relevant to a broker-dealer’s business and enables employees to understand and identify conflicts of interest;

- establish a structure for identifying the types of material conflicts that the broker-dealer and Registered Representative may face, and whether the conflicts arise from financial incentives;

- establish a process to continue identifying conflicts as the broker-dealer’s business evolves;

- provide for an ongoing and regular, periodic (e.g., annual) review to identify conflicts; and

- establish training procedures addressing material conflicts of interest, including how to identify material conflicts of interest and defining employees’ roles and responsibilities with respect to identifying material conflicts of interest;

- “robust compliance review and monitoring systems”;

- “processes to escalate identified instances of noncompliance to appropriate personnel for remediation”;

- “procedures that clearly designate responsibility to business lines personnel for supervision of functions and persons, including determination of compensation”;

- “processes for escalating conflicts of interest”;

- “processes for a periodic review and testing of the adequacy and effectiveness of policies and procedures”; and

- “training on the policies and procedures.”

While, according to the SEC, the proposed Conflicts of Interest Obligation “does not mandate the absolute elimination of any particular conflicts,” the SEC indicated that it believes a broker-dealer generally should establish a “clearly defined and articulated structure for: determining how to effectively address material conflicts of interest identified . . . and setting further a process to help ensure that material conflicts are effectively addressed.” Nonetheless, the SEC also stated its belief that “certain material conflicts of interest . . . may be more appropriately avoided in their entirety for retail customers or for certain categories of retail customers (e.g., less sophisticated retail customers),” and provided as an example “the receipt or payment of certain non-cash compensation that presents conflicts of interest for broker-dealers, for example, sales contests, trips, prizes, and other similar bonuses that are based on sales of certain securities or accumulation of assets under management.” While noting that the payment and acceptance of non-cash compensation is addressed under FINRA rules, the SEC also stated its view that broker-dealers that use these practices should carefully consider whether they can be effectively mitigated so that the broker-dealer can satisfy its best interest obligation.[17]

With respect to material conflicts arising from financial incentives, the SEC indicated that it believes that policies and procedures should include mitigation procedures, but that those policies and procedures can depend on a variety of factors relating to a broker-dealer’s business model, and that certain factors might be weighted more heavily than others. Factors identified by the SEC include the size of the broker-dealer, the retail customer base, the nature and significance of the compensation conflict, and the complexity of the conflict. In addition, according to the SEC, heightened mitigation measures might be required where the retail customer displays a less-sophisticated understanding of investing generally or conflicts involved, where the compensation is less transparent, or for more complex products. The SEC provided guidance about potential practices that might be relevant, including:

- “avoiding compensation thresholds that disproportionately increase compensation through incremental increases in sales”;

- “minimizing compensation incentives for employees to favor one type of product over another, proprietary or preferred provider products, or comparable products sold on a principal basis – for example, establishing differential compensation criteria based on neutral factors (e.g., the time and complexity of the work involved)”;

- “eliminating compensation incentives within comparable product lines (e.g., one mutual fund over a comparable fund) by, for example, capping the credit that a registered representative may receive across comparable mutual funds or other comparable products across providers”;

- “implementing supervisory procedures to monitor recommendations that are: near compensation thresholds; near thresholds for firm recognition; involve higher compensating products, proprietary products or transactions in a principal capacity; or, involve the rollover or transfer of assets from one type of account to another (such as recommendations to rollover or transfer assets in an ERISA account to an IRA, when the recommendation involves a securities transaction) or from one product class to another”;

- “adjusting compensation for registered representatives who fail to adequately manage conflicts of interest”; and

- “limiting the types of retail customers to whom a product, transaction or strategy may be recommended (e.g., certain products with conflicts of interest associated with complex compensation structures).”

We understand that broker-dealers may have considered, and in some cases implemented, many of these conflict mitigation techniques in designing compliance programs for the DOL’s Best Interest Contract Exemption.

Initial Observations

If adopted in its current form, proposed Regulation Best Interest can be expected to raise difficult interpretive and other issues for broker-dealers seeking to comply with the Disclosure, Care, and Conflict of Interest Obligations. Much of this can be expected to result from uncertainty as to how the term “best interest” will be interpreted by the SEC and in FINRA arbitration.

As discussed above, the SEC has not proposed to define “best interest,” and, instead, has stated it would look to “the facts and circumstances of the particular recommendation” and how the broker-dealer complies with the requirements of the Best Interest Obligation. The SEC’s references to “best interest” seem to conflate the common law duties of loyalty and care, resulting in a less precise analytical framework through which to evaluate issues that might arise in making recommendations about securities or investment strategies. For example, it is unclear whether the requirement that a broker-dealer “act in the best interest of the retail customer” requires only that the broker-dealer or Registered Representative refrain from placing their financial interest “ahead of the interest of the retail customer” or whether it requires something more. Similarly, broker-dealers would benefit from clarity as to the importance of cost in recommending a security. In this regard, it is unclear whether cost is the determinative factor in meeting the Care Obligation only when choosing between two securities where “the characteristics of the securities are otherwise identical.” It is also unclear whether a broker-dealer’s receipt of third-party payments may be taken into consideration when making a recommendation where the cost to the investor is the same between different products, and whether different costs need to be considered across product types (e.g., stocks, ETFs, mutual funds, variable annuities), or only within the same product types.

With respect to the Disclosure Obligation, broker-dealers would need to navigate significant compliance and operational issues in ensuring that all material facts about a particular recommendation are reasonably disclosed. While a broker-dealer might be able to disclose some material facts at the outset of a customer relationship, such as through a customer agreement or brochure similar to an investment adviser’s Form ADV, Part 2A, other material facts might need to be disclosed on a recommendation-by-recommendation basis (e.g., specific fees and charges). Broker-dealers would also need to think about how to satisfy the Disclosure Obligation in different mediums, including in-person communications, telephonic communications, and online advice platforms. Each medium presents its own challenges and considerations in determining how to meet the requirements of the Disclosure Obligation while taking into account the associated costs and impact on customer experience. As a general matter, firms may want to consider whether, and to what extent, elements of the disclosures prepared to comply with the DOL’s Best Interest Contract Exemption, and systems for delivering them to customers, could be repurposed for complying with Regulation Best Interest.

The Care Obligation appears to incorporate existing reasonable-basis, customer-specific, and quantitative suitability obligations, but there are some potentially significant changes. First, it would require a broker-dealer to exercise “reasonable diligence, care, skill, and prudence” in satisfying its obligations. It appears that the SEC included this requirement to reflect prudence obligations under ERISA and the DOL’s Best Interest Contract Exemption. This approach, however, would introduce a new concept of prudence that has not been developed in the context of broker-dealer regulation under the federal securities laws. Establishing a prudence obligation raises various interpretive questions, such as:

- Is it consistent with current interpretations of a broker-dealer’s suitability obligations, or does it require something more? If something more, what does it require?

- Does it create liability for failures of diligence, care, skill, or prudence, including by a Registered Representative?

- How does it impact broker-dealers providing one-time advice or advice about proprietary products?

- Does it have a separate impact on the importance of cost or risk in making a recommendation, such as tilting the scale toward lower cost or lower risk products?

The Care Obligation also replaces the concept of suitability with the term “best interest.” As discussed, it is not clear what best interest means and how it differs from existing suitability obligations. Questions with which broker-dealers will need to grapple include:

- How does the new “best interest” concept impact the sale of proprietary products or a limited range of products?

- What is the importance of cost when comparing products that are not “identical?”

- What is the impact on the sale of high-commission products (e.g., structured products, non-traded real estate investment trusts (REITs), non-traded business development companies (BDCs), or variable insurance products)?

In addition, the SEC’s decision to apply quantitative suitability obligations to all recommendations to retail customers, and not just to those where the broker-dealer has actual or de facto control over an account, might raise additional compliance monitoring issues to look for churning across all retail customer brokerage accounts.

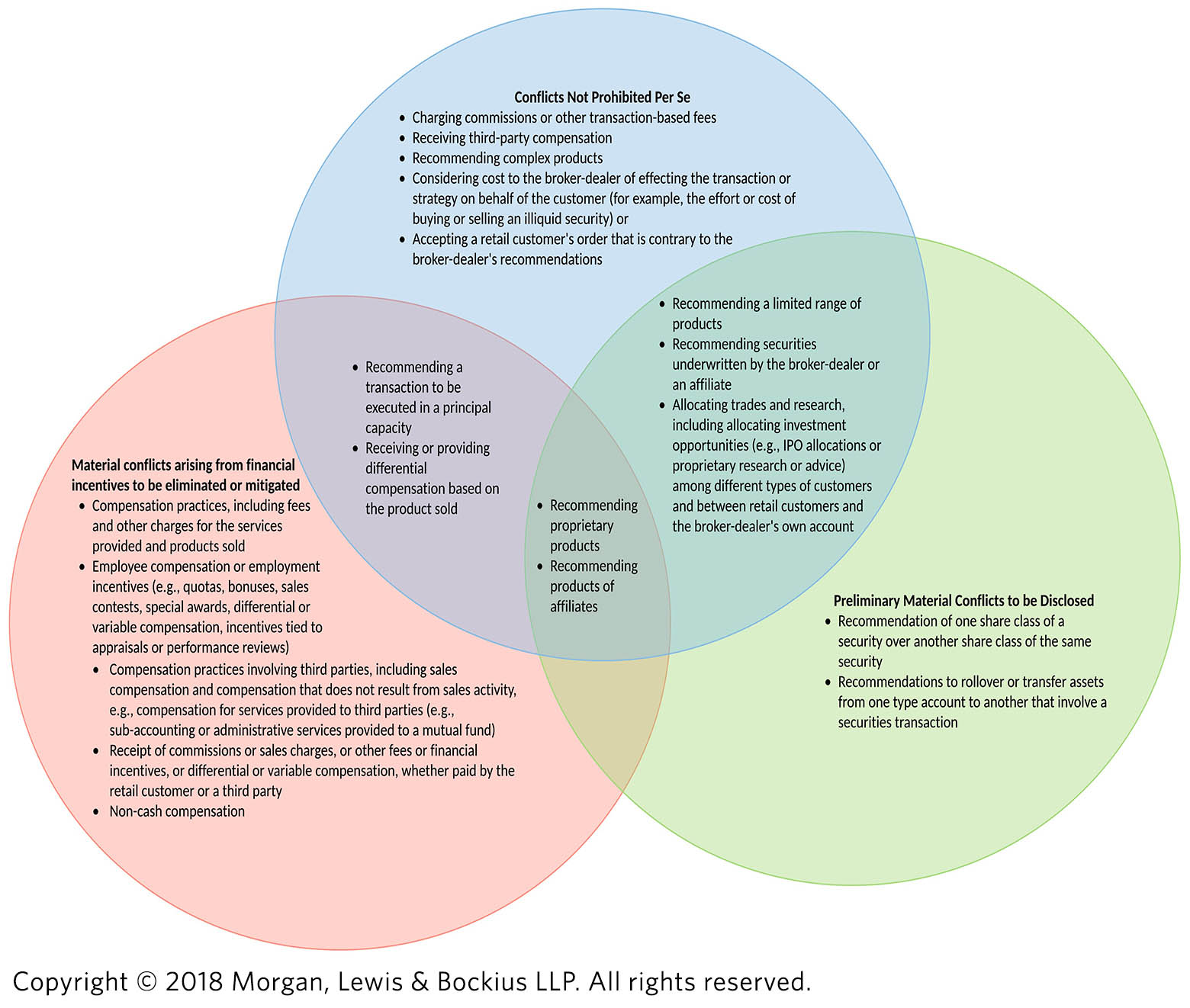

Moreover, the Conflicts of Interest Obligation raises difficult questions as to what types of conflicts that arise from financial incentives can be disclosed and mitigated, or which the SEC might with hindsight view as ones that should have been eliminated. As shown in the diagram below, the examples included in the proposing release do not necessarily line up or provide a clear framework for analyzing how to satisfy the Conflicts of Interest Obligation.

SEC Proposed Approach to Different Conflicts

The direct applicability of Regulation Best Interest to Registered Representatives is also unusual under the federal securities laws.[18] No other SEC rule governing broker-dealers applies explicitly and directly to Registered Representatives. Rather, SEC rules apply to broker-dealers that are registered with the SEC that are responsible for ensuring compliance by persons associated with them under the provisions of the Exchange Act (including provisions pertaining to supervision) and concepts like respondeat superior. After all, Registered Representatives and other employees of a broker-dealer act only as agents of the broker-dealer with which they are affiliated, and their responsibilities when conducting business on behalf of the broker-dealer are derivative—not independent—of the broker-dealer’s obligations. From an enforcement standpoint, it is not clear what is accomplished by having Regulation Best Interest apply directly to Registered Representatives.

Finally, although the SEC stated in the proposing release its belief and intention that Regulation Best Interest would not create any new private right of action or right of rescission—on the basis that it is being proposed, “in part,” under the authority provided by Section 913(f) of Dodd-Frank and Section 15(l) of the Exchange Act (neither of which create a new private right)—aggrieved customers or the plaintiffs’ bar may disagree and argue that Regulation Best Interest is also based on other sections of the securities laws that do provide private rights of action (e.g., Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act). Indeed, the SEC appears to concede its assertion is uncertain, given it requested comment specifically on this point: “Do commenters agree with the Commission’s assessment that no new private right of action or right of rescission is created by Regulation Best Interest?”

Whether the Exercise of Investment Discretion Should Be Viewed as Solely Incidental to the Business of a Broker or Dealer

Finally, the SEC has requested comment on whether it should adopt an interpretation of the broker-dealer exclusion from the definition of investment adviser in Section 202(a)(11)(C) of the Advisers Act that a broker-dealer that exercises investment discretion, other than on a temporary or limited basis, would be viewed as providing advice that is not “solely incidental” to brokerage. Section 202(a)(11)(C) excludes a broker-dealer whose advice is provided “solely incidental” to its brokerage business and who does not receive “special compensation” for that advice. The SEC has considered whether a broker-dealer exercising investment discretion should be subject to the Advisers Act since at least 1978, including in adopted, and since-vacated, Rule 202(a)(11)-1 and a 2007 proposed (but never adopted) interpretive statement about the broker-dealer exclusion. Currently, however, there is no rule or interpretation prohibiting a broker-dealer from exercising discretion over a client’s account.

Initial Observations

Broker-dealers have provided discretionary advice to their customers in exchange for commissions since before the Advisers Act was enacted.[19] Both the SEC and self-regulatory organizations have adopted rules regulating the activities of broker-dealers when exercising discretion over customer accounts.[20] It seems that the same considerations of “preserving investor choice across products and advice models” that underlie proposed Regulation Best Interest apply equally to whether broker-dealers can provide discretionary or non-discretionary services. In addition, considerations of limiting the ability of broker-dealers to provide discretionary services would appear to raise different issues related to “confusion” when dealing with retail customers and institutional accounts.

Contacts

If you have any questions or would like more information on the issues discussed in this LawFlash, please contact any of the following Morgan Lewis lawyers:

Boston

David C. Boch

New York

Christine M. Lombardo

Washington, DC

Thomas S. Harman

Lindsay B. Jackson

Daniel R. Kleinman

Amy Natterson Kroll

Michael B. Richman

Ignacio A. Sandoval

Steven W. Stone

Kyle D. Whitehead

[1] See Regulation Best Interest, Securities Exchange Act Release No. 83062 (Apr. 18, 2018), 83 Fed. Reg. 21574 (May 9, 2018). In a separate release, the SEC also proposed requiring investment advisers and broker-dealers to provide retail investors with Form CRS Relationship Summary (Form CRS) and proposed rules restricting the use of certain names or titles and requiring certain disclosures in retail communications. See Form CRS Relationship Summary; Amendments to Form ADV; Required Disclosures in Retail Communications and Restrictions on the Use of Certain Names or Titles, Securities Exchange Act Release No. 83063, Investment Advisers Act Release No. 4888 (Apr. 18, 2018), 83 Fed. Reg. 21416 (May 9, 2018). The SEC also proposed an interpretation of the standard of conduct for investment advisers under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 and requested comment on three potential ways to enhance investment adviser regulation. See Proposed Commission Interpretation Regarding Standard of Conduct for Investment Advisers; Request for Comment on Enhancing Investment Adviser Regulation, Investment Advisers Act Release No. 4889 (Apr. 18, 2018), 83 Fed. Reg. 21203 (May 9, 2018).

[2] See Commissioner Kara M. Stein, Statement on Proposals Relating to Regulation Best Interest, Form CRS, Restrictions on the Use of Certain Names or Titles, and Commission Interpretation Regarding the Standard of Conduct for Investment Advisers (Apr. 18, 2018); Commissioner Michael S. Piwowar, Statement at Open Meeting on Form CRS, Proposed Regulation Best Interest and Notice of Proposed Commission Interpretation Regarding Standard of Conduct for Investment Advisers (Proposed Rule) (Apr. 18, 2018); Commissioner Robert J. Jackson Jr., Proposed Rulemakings and Interpretations Relating to Retail Investor Relationships with Investment Professionals (Apr. 18, 2018); Commissioner Hester M. Peirce, Statement at the Open Meeting on Standards of Conduct for Investment Professionals (Apr. 18, 2018).

[3] Proposed Exchange Act Rule 15l-1(a)(1).

[4] Proposed Exchange Act Rule 15l-1(b)(1).

[5] Section 913(g) of the Dodd-Frank Act defines “retail customer” as “a natural person, or the legal representative of a natural person, who – (A) receives personalized investment advice about securities from a broker, dealer, or investment adviser, and (B) uses such advice primarily for personal, family or household purposes.”

[6] Although not discussed by the SEC in the proposing release, the concept of “personal, family, or household purposes” is used extensively in related areas of law, including Regulation S-P and various consumer banking laws and regulations (such as the Truth in Lending Act, Regulation Z and Regulation E), the Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act of 1975 (governing warranties on consumer products and defining a “consumer product” as “any tangible personal property . . . which is normally used for personal, family, or household purposes”).

[7] In various circumstances, the staff of the SEC Division of Investment Management has not applied certain provisions of the Advisers Act to advisers when dealing with other investment advisers or financial intermediaries like banks that are subject to fiduciary or other suitability obligations. See, e.g., BNY ConvergEx Group, LLC, SEC Staff No-Action Letter (Sept. 21, 2010); Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP, SEC Staff No-Action Letter (Apr. 16, 1997); Copeland Financial Services, Inc., SEC Staff No-Action Letter (Sept. 21, 1992); Kempner Capital Management, Inc., SEC Staff No-Action Letter (Dec. 7, 1987).

[8] Proposed Exchange Act Rule 15l-1(a)(2)(i).

[9] Proposed Form CRS would require broker-dealers, investment advisers, and dual registrants, when interacting with retail customers, to provide a maximum four-page form disclosure document describing the brokerage and advisory services provided, as applicable, including fees, conflicts, service levels, and standards of conduct, and include sample questions for investors to ask their financial professional to better understand the services offered.

[10] See Securities Indus. Ass’n, SEC Staff No-Action Letter (Dec. 16, 2005).

[11] Proposed Exchange Act Rule 15l-1(a)(2)(ii).

[12] FINRA Rule 2111, however, does not require scienter.

[13] The term “retail customer investment profile” would be defined similar to “customer’s investment profile” in FINRA Rule 2111, to include “the retail customer’s age, other investments, financial situation and needs, tax status, investment objectives, investment experience, investment time horizon, liquidity needs, risk tolerance, and any other information the retail customer may disclose . . . in connection with a recommendation.” Broker-dealers would also be required to maintain and preserve records of information collected and provided to the retail customer, as well as the Registered Representative responsible for the account. See Proposed Exchange Act Rules 17a-3(a)(25), 17a-4(e)(5).

[14] FINRA has similarly requested comments on a proposed amendment to Supplementary Material .05(c) of FINRA Rule 2111 to remove the control element from the quantitative suitability obligation. See Quantitative Suitability, FINRA Regulatory Notice 18-13 (Apr. 2018).

[15] Proposed Exchange Act Rule 15l-1(a)(2)(iii)(A).

[16] Proposed Exchange Act Rule 15l-1(a)(2)(iii)(B) (emphasis added).

[17] See FINRA Rules 2310, 2320, 2331, 5110.

[18] The DOL’s fiduciary rule and Best Interest Contract Exemption (and other related exemptions) would have applied to employees, independent contractors, agents, and registered representatives of a financial institution.

[19] See, e.g., SEC, Report on the Feasibility and Advisability of the Complete Segregation of the Functions of Dealer and Broker at 76 (June 20, 1936) (discussing various services provided by broker-dealers, including management of trust assets and handling of discretionary accounts as part of commission-based brokerage).

[20] See Exchange Act Rule 15c1-7; Exchange Act Rule 17a-3(a)(6)(i), 17a-3(a)(7); FINRA Rule 5121(c); NASD Rule 2510; MSRB Rule G-22(b); MSRB Rule G-27(c)(i)(G).