Federal Circuit Tosses Columbia’s $3M Design Patent Infringement Award Without Resolving Damages Issue

November 20, 2019While sidestepping the anticipated “article of manufacture” issue for calculating the infringer’s total profits under 35 USC § 289, the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in a recent precedential opinion overturned a district’s court grant of infringement on summary judgment, and found that incorporating a logo in the accused design may prevent a finding of infringement. The decision makes clear that design patent infringement must be tried to a jury where factual disputes exist that could inform an ordinary observer’s overall impression of a design.

Design patent practitioners had been anticipating Federal Circuit guidance on design patent damages. Instead, on November 13, the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit set aside a finding of design patent infringement in Columbia Sportswear N. Am., Inc. v. Seirus Innovative Accessories, Inc.,[1] holding that the district court improperly excluded a logo from its infringement analysis and resolved disputed factual issues that should have been reserved for a jury.

Background

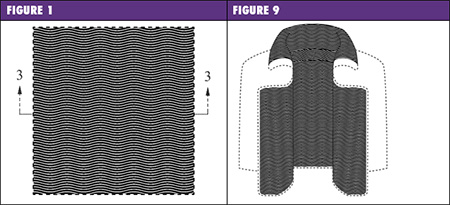

In January 2015, Columbia brought suit in the District of Oregon accusing competitor Seirus of infringing two patents, including US Design Patent No. D657,093 (the ’093 Patent), that protect its “Omni-Heat” technology—a material that reflects body heat and wicks moisture. Specifically, the ’093 Patent is drawn to the “ornamental design of a heat reflective material” as applied to various articles, including sleeping bags, boots, pants, gloves, and jackets.[2]

Columbia alleged that certain “HeatWave” products—the moisture-wicking, heat-reflective material used in Seirus’s cold-weather gear—infringed the Omni-Heat patents, including the ’093 Patent.

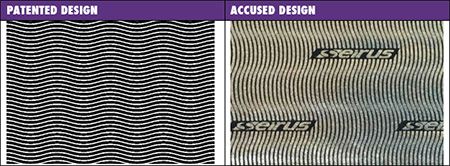

After the district court declined to give a textual construction to the patented design, Columbia moved for summary judgment that Seirus’s HeatWave products infringed the ‘093 Patent. As part of its infringement analysis, the district court considered the designs side by side and found that “even the most discerning customer would be hard pressed to notice the differences between Seirus’s HeatWave design and Columbia’s patented design.”[4]

For its part, Seirus identified several differences between the designs that it argued created a factual dispute, including that the waves in the accused design were repeatedly interrupted by Seirus’s logo, and that the waves varied in terms of orientation, spacing, and size—but the district court disagreed.[4] Relying on LA Gear, Inc. v. Thom McAn Shoe Co.[5] and its progeny, the district court declined to consider Seirus’s logo placement in its infringement analysis, noting that it is “well-settled that a defendant cannot avoid infringement by merely affixing its logo to an otherwise infringing design.”[6] As for the vertical rather than horizontal orientation, the court discounted this argument because the ’093 Patent did not require a particular orientation; the design can be oriented in any direction depending on how it is held.[7] And as for wave spacing and size, the court found that those differences were not claimed in the patent and were irrelevant to its analysis.[8] Even considering the differences, however, the district court found them to be “so minor as to be nearly imperceptible” and that they did “not change the overall visual impression that the Seirus design is the same as Columbia’s patented one.”[9]

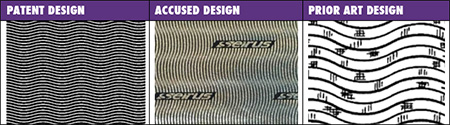

To complete its analysis, the court considered Seirus’s submitted prior art designs, and after identifying the closest prior art design, found Columbia and Seirus’s designs to be “substantially closer” than the pattern disclosed in a prior art, as shown in this comparison chart.[10]

Based on these findings, the district court held that “[a]n ordinary observer familiar with the prior art would be likely to confuse Seirus's design with Columbia's patented design.”[11] In a subsequent jury trial on damages, Columbia was awarded $3,018,174 as “Seirus’ total profit from sales of the relevant article of manufacture” under 35 USC § 289.[12]

The Federal Circuit Decision

On appeal, the Federal Circuit vacated the summary judgment decision for two reasons: “(1) the court improperly declined to consider the effect of Seirus’s logo in its infringement analysis and (2) the court resolved a series of disputed factual issues, in some instances relying on an incorrect standard, that should have been tried to a jury.”[13]

First, the Federal Circuit found that the district court’s reliance on LA Gear to “wholly disregard” the Seirus logo was misplaced because “copying was admitted” in that case. Put differently, LA Gear held that “[a] would-be infringer should not escape liability for design patent infringement if a design is copied but labeled with its name,” but “LA Gear does not prohibit the fact finder from considering an ornamental logo, its placement, and its appearance as one among other potential differences between a patented design and an accused design.”[14] According to the Federal Circuit, the fact finder cannot “ignore elements of the accused design entirely” because the fact finder must determine “whether an ordinary observer would find the effect of the whole design substantially the same.”[15]

Second, while Seirus pointed to differences in uniformity of wave thickness between its products and the patented design, the district court found that wave thickness to be unclaimed—a determination that was found erroneous at the Federal Circuit. The district court also noted that, in any event, such a distinction in wave thickness would not affect the overall visual impression that the Seirus design is the same as the patented design. The Federal Circuit found that the district court’s “piecemeal approach” to determining infringement—i.e., “considering only if design elements independently affect the overall visual impression that the designs are similar”—was “at odds with [its] case law requiring the fact finder to analyze the design as a whole.”[16] As for evaluating the prior art, the Federal Circuit likewise found that “the court erroneously compared Columbia’s design, Seirus’s HeatWave product’s design, and a prior art patent design side-by-side before concluding that ‘[t]he overall visual effect of the Columbia and Seirus designs are nearly identical and if the logo was removed from the Seirus design, an ordinary observer would have great difficulty distinguishing between the Seirus and Columbia designs.’”[17]

Importantly, the Federal Circuit held that even if the correct standard were applied, the summary judgment decision would still be improper because “the district court made a finding of fact—whether an element of Seirus’s design would give an ordinary observer a different visual impression than Columbia’s design—over a disputed factual record,” which is “not permitted by Rule 56 and should be resolved by the jury on remand.”[18]

Future Implications

The Federal Circuit’s Columbia decision reinforces the notions that design patent infringement is a question of fact for juries to resolve and that district courts should carefully consider whether there are potential disputed facts that could inform an ordinary observer’s overall impression of a design before deciding infringement by summary judgment. In Columbia, the factual dispute centered on whether certain differences between the accused design and the patented design (e.g., logo placement, wave thickness, orientation) would give a different visual impression to the ordinary observer. The Federal Circuit also criticized the manner in which the district court used the prior art to reach that conclusion. It did not, however, clarify how the district court should have applied the teachings of the prior art in this analysis. Nor did the Federal Circuit provide further guidance on the limits of other factual disputes that could impact the propriety of summary judgment,[19] a tool used to avoid unnecessary jury trials where there’s no triable issue of fact.

By vacating the infringement finding, the Federal Circuit also left unanswered “additional issues relating to the court’s damages award under 35 U.S.C. § 289” that even the Columbia court recognized as “important”—namely, whether “the § 289 remedy is one of disgorgement that should be tried to the bench,” and “whether the proper article of manufacture in this case should be the HeatWave product actually sold or the fabric encompassing the design.”[20]

For applicants, the effective depiction of logos incorporated into a design may prove helpful. For example, illustrating logos in broken line, rather than omitting them entirely, may in some instances reinforce the optional relationship between a design and possible logo placement.

Additionally, although often thought to be narrowing, applicants should consider claiming more of the design, in at least one filing, to help diminish the emphasis on particular differences in the partial design(s). Protecting more of the article of manufacture may also preserve the ability to collect damages should changes in the law eventually limit damage awards for certain partial designs. A robust filing strategy continues to include protecting the overall design and various portions thereof.

Contacts

If you have any questions or would like more information on the issues discussed in this LawFlash, please contact the authors, John L. Hemmer (Philadelphia), Kenneth J. Davis (Philadelphia), and Michael J. Lyons (Silicon Valley), or any of the following lawyers:

Boston

Joshua M. Dalton

Chicago

Scott D. Sherwin

Jason C. White

Houston

C. Erik Hawes

Philadelphia

Louis W. Beardell, Jr.

San Francisco

Brent A. Hawkins

Brett A. Lovejoy, Ph.D.

Carla B. Oakley

Silicon Valley

Dion M. Bregman

Douglas J. Crisman

Andrew Gray IV

Washington, DC

Eric S. Namrow

Collin W. Park

[1] Columbia Sportswear N. Am., Inc. v. Seirus Innovative Accessories, Inc., Nos. 2018-1329, 2018-1331, 2018-1728, 2019 WL 5938886 (Fed. Cir. Nov. 13, 2019) (the Federal Circuit Decision).

[2] Columbia Sportswear N. Am., Inc. v. Seirus Innovative Accessories, Inc., 202 F. Supp. 3d 1186 (D. Or. 2016) (the Summary Judgment Decision).

[3] Summary Judgment Decision at 1189.

[4] Federal Circuit Decision at *7-8.

[5] 988 F.2d 1117 (Fed. Cir. 1993).

[6] Summary Judgment Decision at 1193-94.

[7] Federal Circuit Decision at *7.

[8] Id.

[9] Id.

[10] Id. at 8.

[11] Summary Judgment Decision at 1197.

[12] Columbia Sportswear N. Am., Inc. v. Seirus Innovative Accessories, Inc., No. 3:17-cv-01781, ECF No. 377 (C.D. Cal. Sept. 29, 2017).

[13] Federal Circuit Decision at *8.

[14] Id. (emphasis in original).

[15] Id. (quoting Gorham Mfg. Co. v. White, 81 U.S. 511, 530 (1871) (emphasis added)).

[16] Id.

[17] Id. at *8-9.

[18] Id. at *9.

[19] The Federal Circuit also highlighted Seirus’s argument that the identity of the ordinary observer was a factual dispute to be resolved by a jury. But, the court did not go so far as to single out that dispute as dispositive.

[20] Federal Circuit Decision at *9.