If your organization has faced a Medicare audit in the last decade, you may have experienced a significant delay in the Medicare appeals process due to a monumental backlog of claims pending in front of administrative law judges (ALJs). As a result, the Office of Medicare Hearings and Appeals (OMHA) has initiated several pilot programs and received a significant boost in funding following a federal court decision requiring OMHA to develop a plan to reduce this backlog.

Ultimately, after approximately a decade of being behind the eight-ball, OMHA has finally eliminated this longstanding backlog. Now, appeals that once sat dormant for anywhere from three to five years before being heard are receiving attention in a matter of just a few weeks to months.

Fundamentally, these changes are a positive step forward in improving the efficacy of the Medicare appeals process by providing appellants with greater access to a live tribunal and speedier decisions from ALJs. However, some questions remain: how did OMHA successfully eliminate this backlog? And, more specifically, what did OMHA do with all of its supplemental funding, and what are the ongoing effects of that funding?

Changes Within OMHA

Perhaps most notable among its operational changes, OMHA appears to have hired dozens of new ALJs with varying levels of experience, background, and training, as well as opened up several additional field offices from which ALJs can adjudicate appeals.

We’ve been before numerous ALJs over the last decade as we have helped hospices and other healthcare providers navigate through the Medicare appeals process, but many of the ALJs we’ve encountered in the past year are new. While this is not an unwelcome change, it will have some important effects on the ALJ hearing process and how providers prepare for these hearings.

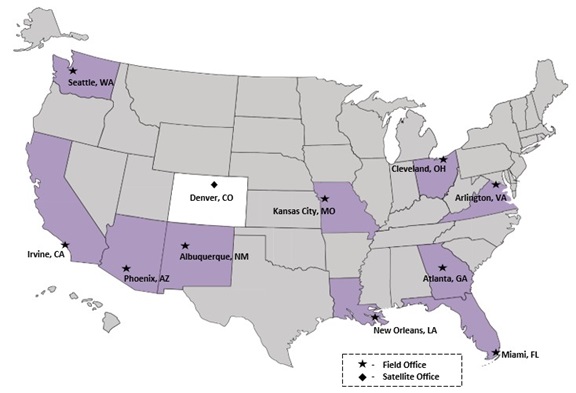

Map of OMHA Office Locations

With the added program funding, OMHA has expanded from 4 to 11 offices across the United States.

First and foremost, providers should not assume that their assigned ALJ has prior experience with their specific types of claims. With this in mind, providers can benefit from discussing with an ALJ some basic context around their services, and, although beneficial for any provider, this is particularly useful when grappling with the relatively unique coverage criteria and technical requirements associated with hospice claims.

While this does not mean that ALJs need to be read the Medicare Local Coverage Determinations (LCDs) or the Medicare Program Integrity Manual, ALJs can often benefit from clinical discussions regarding the relative weight of certain clinical factors on the prognostication process. In the hospice context, using a physician—especially the certifying physician—to make this point is a highly effective method for not only education purposes, but also as a means to establish credibility with the ALJ on the process that a hospice uses to certify and recertify patients.

Second, and relatedly, providers should nevertheless be careful not to overlook the importance of LCDs. Although hospice LCDs clearly state that the intention is to provide clinical guidelines, LCDs are in fact given much greater weight by ALJs when adjudicating claims—often treated as coverage requirements. This, of course, makes sense: ALJs are not usually medical doctors and thus do not have any personal experience to rely on when, in essence, deciding whether a patient is terminally ill. Accordingly, ALJs often closely follow the LCDs when making determinations about eligibility. This doesn’t mean that any patient falling outside of an LCD is a lost cause; rather, this attention to LCDs instead means that providers should prepare to present additional compelling documentation of the physician’s clinical judgment and place a focus on disease progression during the hearing.

Finally, while the hearing itself is an important piece in presenting the provider’s case and will help shed light onto “gray area” patients, the ultimate decision will not be issued during the hearing itself. Instead, the ALJ and their team of attorney advisors will pore over the clinical records, hearing testimony, and any other evidence presented in the case to decide whether a particular claim is favorable.

This means that, while compelling hearing testimony is important, it is equally important for providers to ensure that any clinical documentation is easy to read and evidences the relevant clinical facts that physicians used to establish eligibility for hospice. This may be done through summary statements, highlights in the existing administrative record, or by describing the information during the hearing itself.

While ALJs will give deference to a certified physician’s clinical judgment, ALJs often require corresponding, reasonable supporting documentation that demonstrates how the physician reached that determination. And, of course, the closer the patient’s case is to the LCD, the greater likelihood of success.

Looking Ahead

While this new crop of decisionmakers at OMHA presents certain challenges, it also presents new opportunities for appellants to provide ALJs with education and context in support of disputed claims. As a result, it remains critical for providers to pursue their appeal rights in all instances in which there is a good-faith basis to do so.

Further, when pursuing an appeal, providers must ensure the appeal highlights each patient’s full clinical condition (i.e., their overall clinical picture) and not just the patient’s primary diagnosis. After all, what may present as a minor clinical factor in the eyes of one reviewer, may be dispositive to another.

Questions about the Medicare appeals process or hospice compliance? Contact us or your Morgan Lewis lawyers for more information.